Bates Hall at the Boston Public Library

One of the most effective metaphors for evolutionary change is the image of an exploration of a space, perhaps a map that shows "fitness peaks" or, better, a library of possibilities. The philosopher Daniel Dennett, writing in Darwin's Dangerous Idea, suggested The Library of Mendel as a way of thinking about the total set of possible gene sequences. He was adapting an idea famously employed in a short story by Jorge Luis Borges called "The Library of Babel," which consists of the total set of possible books of a particular length. (This "library" exists on a website designed for creators and researchers.)

Contemplating a space of possibilities—whether that space consists of books written in English (26 letters), or "books" written in the language of DNA (four letters), or "books" written in the language of protein (20 letters)—is both fun and dizzying. The dizziness is induced (for me, at least) by the vastness of these libraries (Babel or Mendel, doesn't matter). How vast? Here is how Dennett describes the Library of Babel's size (italics are his):

No actual astronomical quantity (such as the number of elementary particles in the universe, or the amount of time since the Big Bang, measured in nanoseconds) is even visible against the backdrop of these huge-but-finite numbers. If a readable volume in the Library were as easy to find as a particular drop in the ocean, we'd be in business!

—Darwin's Dangerous Idea, p. 109

Dennett then uses Vast to indicate "Very-much-more-than-astronomically" large and Vanishingly small to indicate the likelihood of something like discovering a "volume with so much as a grammatical sentence in it" in the Library. In other words, we lack words to adequately describe the size of the Library and the improbability of randomly discovering anything coherent inside it.

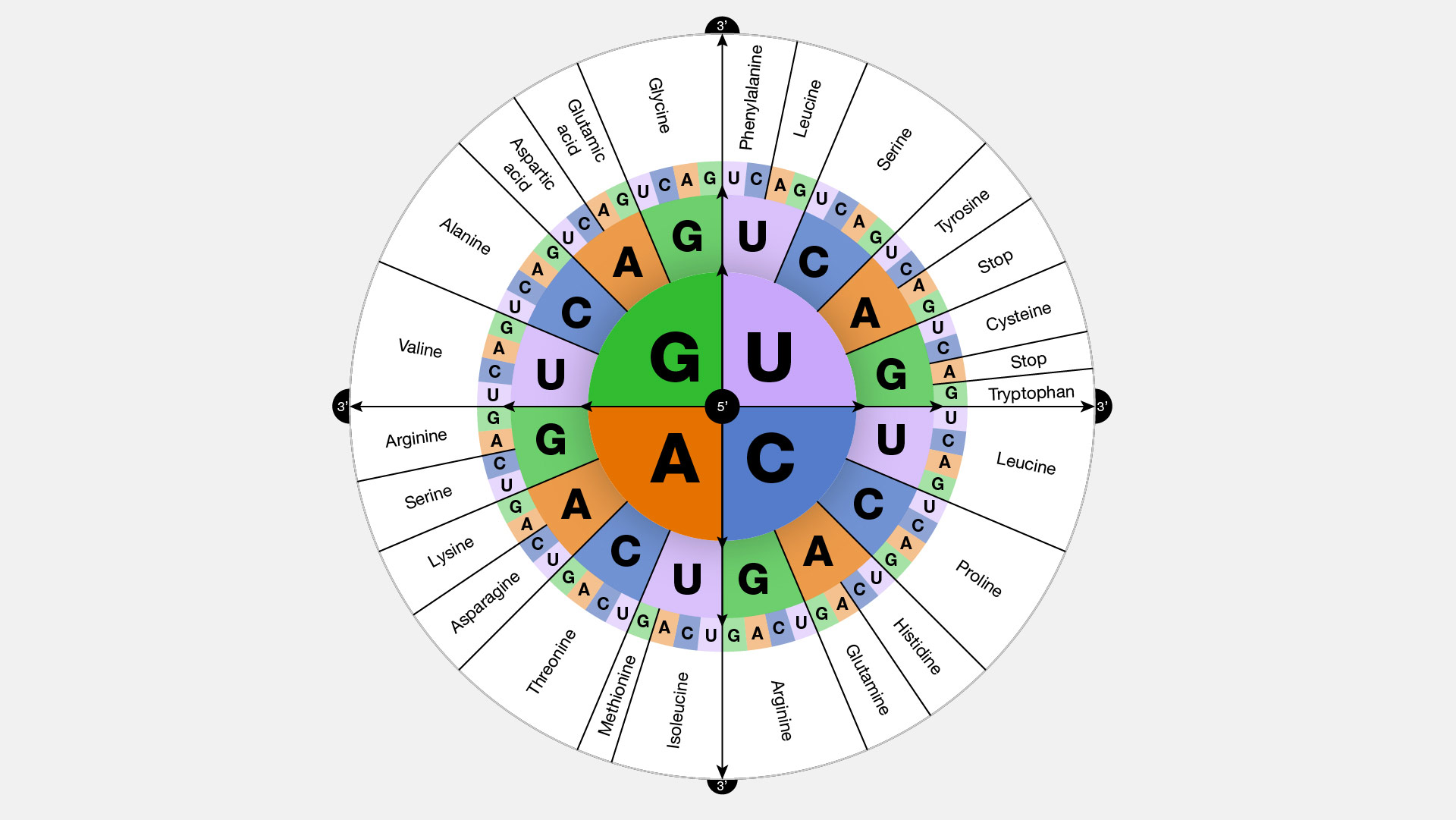

|

| The genetic code (from genome.gov) |

And that is the library that evolution has been exploring for the last 4 billion years or so. I don't have the math handy but if you work it out, I think you will find that evolution could not have visited even a Vanishingly small subset of the library. One oft-cited paper compared the problem to the "problem" of Deep Blue learning chess moves.

It would be natural for this kind of reflection to cause us to think—or to feel—that evolution has accomplished something so improbable that it is effectively impossible. That accomplishment: finding and creating (or actualizing) many tens of thousands of functional proteins, some of which are undisputed marvels of design, in a Vast library of possibilities. Following the reasoning applied to the Library of Mendel and the Library of Babel, we reasonably assume that the number of functional proteins in the Library is Vanishingly small. We seem to have every reason to think and feel that evolution is hard, that it accomplishes the effectively impossible.

But let's think again about that. Do we know that functional proteins are Vanishingly rare? We have one big clear reason to doubt that: in less than a billion years, functional proteins were discovered and put to work running life on earth. This means that evolution found some jumping-off points that it could use to explore the library with some of its famous tools: small change followed by selection. In other words, as reasonable as it is for us to sense that evolution is hard, its success in finding function in the Library of Crick should make us suspect otherwise.

In fact we have new insights into the Library of Crick, some facts that erode the mythology of a vast library full of useless gibberish. We know that evolution doesn't randomly sample from the library, that its gradual and incremental nature is actually the opposite of a random sampling. But we also now know that the library itself is far richer than we used to think.

Winning the lottery at the Library of Crick is hard. Change, we all agree, is hard. Evolution is easy.

Image credits: Boston Public Library from Wikipedia; image copyright ©2005 by Daniel P. B. Smith and released under the terms of the GFDL. Genetic code from Genome.gov.

No comments:

Post a Comment